The Ethical Method of Repair

The Attention is in the Details

RON BARBAGALLO:

There is no glitter that plays with the souls of film fanatics like the art produced by the Walt Disney Studio. The films made by Disney hold an emotional spot in the hearts of their fans and this is not by accident. Their characters are drafted to connect to how we feel about ourselves and where we feel we fit within our own lives. The good-versus-evil plot lines that come out of Disney sell us the fantasy that people in power are punished when they try to hold other people back, and the way these narratives are designed to exploit our need to believe in these happy endings has created a cash machine for Disney that is almost unique in the realm of big box office animation.

But on the other side of Disney lies the history of the studio.

Not just the history of its art — but the history of its corporate culture.

And there is no study of what happened to the production art made by Disney that isn’t intertwined with its corporate culture, and how the culture at Disney was affected by the Union Strike of 1941.

Before the strike, the studio cultivated top-tier talent and these artists were the tools Walt Disney used to rachet up the aesthetics of animation. Aesthetics Walt Disney lifted from the live-action cinema of the day. And from these live-action movies, Walt took emotive character performance, musical scoring, meaningful songs, and art direction and he imbued these qualities into the vaudeville-like animated aesthetic that was the norm in the 1920s.

But with success came money, and the artists who did the work for Walt Disney wanted to share in the profits they felt they helped create. This led to a rift between Walt Disney and the people who helped him achieve his goals. When the strike that followed ended, so did the creative arch the studio was on. In the strike’s aftermath, Disney lost a good deal of the innovators who set up his aesthetic. And to make matters worse, because of WWII, Disney also lost a significant amount of overseas revenue. Revenue that was paying for the excesses of Walt’s art for art’s sake way of doing business.

In the wake of these events, Disney animated features would take an artistic step backward in order to regain their footing, and in the post-1942 Bambi (David Hand, 1942) era, you see that a number of “package pictures” were made. Feature films like Saludos Amigos (Norman Ferguson, 1942), Make Mine Music (Jack Kinney et al, 1946), Melody Time (Clyde Geronimi et al, 1948), Fun and Fancy Free (Jack Kinney, Bill Roberts et al, 1947), and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (Ben Sharpsteen et al, 1949) to name a few that included a number of shorter animated sequences.

These full-length films were not an effort to fill the screen with one larger than life children’s fairy tale like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1937) or Pinocchio (Ben Sharpsteen, 1940), or Bambi (David Hand, 1942). Rather, these features were made up of shorter animated segments that were made using reduced budgets. These budget cuts caused the studio to simplify the aesthetics they were using pre-strike. And it is in this time period, like the Silly Symphonies in the 1930s, that these “package pictures” became a sort of unplanned testing ground to get this next version of the Disney aesthetic fully functioning.

But there was a problem.

The “package pictures” made between 1943-1949 failed to bring in the money that was needed to sustain the making art for art’s sake business model that put Disney on the map, and this is where Walt’s brother Roy O. Disney came into play.

Under Roy O.’s influence, the storytelling and the performance animation innovated pre-strike were simplified and commercialized. The intention of their films went from making striking artistic statements and Disney became a machine that pumped out similar before-middle-and-end storylines that included character animation that was less about nuanced performance and instead used caricature rather broadly to make its point. Starting with Cinderella, (Wilfred Jackson, 1950) which was released in 1950, their new string of less artistically ambitious Disney animated features contained mostly one sort of narrative, and the profits generated by this new formula became something the studio could rely on.

And this shift to dumbing things down into a formula so they could make money was not the only thing that manifested during this phase of the studio.

To the studio’s new assembly line, a corporate reward system of sorts was added. One that groomed the employees who remained after the strike and trained them — that if they did what they were told (unlike the innovators who challenged the studio’s management), they would stay employed, and if they survived the power plays at the studio (from other artists and from management), they could aspire to become like one of “The Nine Old Men.” Artists who to a great extent were largely copying the aesthetic created by the pre-strike artists, and artists who thanks to the efforts of Disney publicity still occupy a wildly disproportionate level of importance in the minds of Disney fans.

Why do I bring this up?

Because the idea of doing what you’re told and using people who have been groomed to work in this sort of system factor significantly into what happened to the Art History of Walt Disney Production Art.

So, let’s start by explaining what “Production Art” is and why what “Production Art” is valuable.

If you look at any Animation Art auction catalog, you will find that the artifacts that leave Disney are sold to the public by describing them as one thing: “Production Art.”

The use of that specific adjective and that specific noun means one thing: the history of the artifact at the time when it was photographed at Disney and as you see it in a Walt Disney film or short.

To the hearts and souls of Disney fans, when one of them buys a piece of “production art” it is because they want to own that particular moment in the film history. A moment they can freeze-frame when they watch the film and say to themselves “I own this.”

With the Production Drawings and the Production Concept Art made for Disney films, it is not typical that you see a disconnect from what the artifact was during its role in production and how it looks today.

But you will see that severe alterations were made to Disney Production Cels and Production Background Paintings - the very images you see when you watch one of their films.

And the reason for that is because Disney allowed people who were on hand, people they liked, people who were not trained to do the work they were taking on, to take on the task of altering the studio’s art history so the art could be sold to the fans of their films.

So how did this get started?

The answer is rather innocently: the studio went to someone who was working for them who had no knowledge about making decisions concerning the longevity of their materials. But she knew how to work within the culture of the studio.

Due to this, it can be no surprise that Disney cel inker and painter Helen Nerbovig was left to have to pull from what she did know, and to discuss what she did know, I will allow her sister Buf E. Nerbovig and her husband Robert J. McIntosh (who were both Disney employees) to speak about Helen.

To do this, allow me to pull from 17 pages of transcribed but unpublished interviews I did with Buf E. Nerbovig and Robert J. McIntosh in the summer of 1997.

Robert J. McIntosh:

“She [Helen] grew up in San Diego and Los Angeles and as a child, she was already interested in art. She won the Hollywood Bowl Easter poster contest. An original artwork Helen did. [It was] her impression of a cat; it is really in the art nouveau, art deco style of the twenties and early thirties. Again, that’s done with airbrush and stencils which she ended up using in the Disney setups. It is something I want to give her credit for in that [regard]. That she took cels and she united them to the elements that she was adding to them. They don’t appear that way in the film. She made them into a piece of artwork by using what was left around, using these different papers and the wood veneer but she united everything together with an airbrush glazing of shadowing on top of let’s say a cel of Dopey, [which] may have been trimmed into a circle and applied to a wood veneer.”

“Before Courvoisier I believe Helen made up special cel setups for either friends or business associates of Walt’s. The girls [the women Helen worked with in Ink and Paint at Disney were] all enthused over these setups and [they] urged her to show them to Walt. So she would take these things up to him. There was some lapse of time there between the first setups that Helen made and the time when Courvoisier began the distribution.”

Buf E. Nerbovig:

“At the end of Snow White [and the Seven Dwarfs] they were getting the stuff ready for the morgue to hold scenes and backgrounds and everything. And that’s when Helen put together a beautiful setup to give to Walt for his office.”

“We used to go back and forth and take watches home [from Walt to our father]. Walt collected music boxes and he used to send those home because my Dad was also a watchmaker. Dad repaired these things. So we went back and forth to Walt’s office quite often and it wasn’t too unusual that Helen would make a beautiful setup and give it to Walt for his office.”

“Well, then [Guthrie] Courvoisier, who had a little gallery where he sold prints and stuff, he saw the setup in Walt’s office and said that he could certainly merchandise it and make some money. So he got that [a contract to distribute the art] and then they had Helen get a bunch of girls together and she had a little room [at Disney] which was called The Cel Setup.

Robert J. McIntosh:

“The best cels were made using the original production backgrounds. You see, they [the cels and backgrounds] were all kept in the morgue stacked together. In other words, each scene would have a stack of cels, inked and painted animation cels with the production background. Helen made the first setup with the production background. Maybe Snow White and the Prince at the wishing well, or something like that. Well, you have maybe a few dozen very nice cels from the same scene but you’ve already used the production background. That’s how the stenciled [airbrushed] backgrounds came about.

Helen designed a simplified version of the background by cutting cels of the objects [making friskets], you know [of] a tree, and maybe the wishing well, and [for] the sky, a cloud or two. In other words, she greatly simplified. Helen did this by cutting stencils [friskets]. Helen designed everything that went into these first cel setup. She made the first prototype. When they needed more backgrounds, that’s where the twenty girls came in. Under Helen’s direction, they cut the cels [down around the character or they cut the sheets down], and [they] made replica backgrounds and assembled these cels using rubber cement.

[Another] one of the first ones [cel setups], one of the backgrounds for the dwarfs. Helen got actual thin wood veneer, shaved wood glued to board. And she would simply cut a stencil of the dwarf and then [she would] spray with black airbrush, [a] dark airbrush spray [to indicate] shadows on [the cel and on] the wood background and immediately it had dimension. The dwarfs seem to be casting a shadow on the wall.

The wood veneer was available in shops that featured art papers. I remember way back there was a paper dealer on 7th Street near Art Center School. McManus and Morgan, I remember going there a few times at least and they had a wonderful selection of quality papers and these art papers. I think sometimes a paper would be done with wood blocks with one or more colors.

The cel setups, she [Helen] continued doing them I believe through Pinocchio, Fantasia and Bambi.

On Tuesday, February 21, 2017, the Walt Disney Museum published on their website an article by Tracie Timmer, Education Coordinator at The Walt Disney Family Museum. In that article, the author states:

“In addition, when Roy Disney priced out the cost of paying the artists and the supplies needed to prepare the art, he realized that this method was not particularly cost-effective. Roy decided that after the release of Pinocchio in early 1940, he would ask Courvoisier to take over the task of preparing the artwork for sale. This Guthrie did willingly, and hired art students in San Francisco to help them with the task.”

I talked with Buf E. Nerbovig about this very topic when I interviewed her and she had this to say:

Buf E. Nerbovig:

“No! It didn’t stop then. It was into the 40’s. They wouldn’t ship all that stuff out someplace else. And, [as] you know, the cels have to be handled so carefully. He wouldn’t have known what to do with them or how to. He [Guthrie Courvoisier ] only put his name on it as a distributor. I mean that’s actually all he should have done. No, it was all done in the studio, every bit. He never made any backgrounds.”

I also asked Buf E. Nerbovig about the lamination of the Disney cels which given what the Walt Disney Museum article states would have been done in San Francisco. And Buf E. told me “Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah.” That the art was laminated at Disney, not in San Francisco, and for the reason she stated above.

Because the lamination of Disney art happens after the release of the art from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, I asked Buf E. Nerbovig what cel setups do you recall Helen working on?

Buf E. Nerbovig:

Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi, Dumbo. I know she worked on Cinderella too. It only could be done [at the studio] when they were getting stuff ready for the morgue, you know. Where they saved anything at all. It had to. You have no idea how tenderly they [the cels] were handled and how if any of the inked lines popped off, they had to be put back on. Had to be the right number [of Disney] ink and all that sort of thing. You know, it wouldn’t be anything anybody could do on his own unless they were given all that information and could read exposure sheets and that sort of thing.”

And Buf E. Nerbovig is right about this.

From my 36 years of direct experience, I can tell you the materials used to prepare the art and how the technical preparations that were done to the art do not change during the entire time Disney art was prepared so it could be sold through Courvoisier. The papers and boards are the same. The various tapes placed on the setups are the same. The backing boards are the same. The clear sheets used to cover the artwork often have Disney punch in that plastic and are identical plastics to Disney cel sheets. The clear sheets used to do the lamination are clear Disney cel sheets that often have Disney punch on the clear cel sheet. The only way you can get those clear cels with the unique Disney punch is from Disney. The so-called adhesive used at Disney from the beginning of when Helen started to prepare the art is also the same throughout all the Courvoisier releases, and it is not rubber cement (even if it was sold to them as that as Robert J. McIntosh states). If the art was prepared by art students in San Francisco as the Walt Disney Museum article states, they would have had to be using the same supplies and in the same way Helen and her team did.

I emailed the Walt Disney Museum asking for the author to send me the sources she used to draw her conclusions but did not hear back.

In regard to Buf E. Nerbovig and Robert J. McIntosh and what they have to say, I feel that they may be

similar to Disney staffer and Ink and Paint person Ruth Tompson, who in Mindy Johnson’s book Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney's Animation drew a rather wild conclusion about Mary Weiser suggesting Weiser was a professional paint chemist - when maybe a big part of what Tompson was doing when she spoke was eulogizing someone she knew.

With Tompson, you are taking the word of someone who is not a chemist to judge the acumen of someone the studio assigned the task of taking on the role of paint chemist, and there are scientific ways to substantiate the sort of alterations to the paint that anyone might suggest happened at this time. None were provided to substantiate this claim, and I can tell you from firsthand observation, you won’t find a substantial shift in paint chemistry during the time when Weiser was told to play with the paint.

Additionally, I want to point out that Weiser states in the Mindy Johnson book that Disney paint “was more finely ground than most.” I can tell you just the opposite is true. If you look under 5x or 10x magnification and compare Disney gouache along side Cartoon Colour cel vinyl, the pigment grind of Disney gouache is much larger and much more random and abstract in its chunkiness. I have verified this with Patti Griffith, owner at Cartoon Colour Company, Inc. and the wife of their paint chemist and she laughed at Weiser’s claim.

I know from Edward Bianchi, the son of Emilio Bianchi, (and someone who assisted his father in the Disney paint lab on the weekends), that Emilio was recruited from Kodak where he was working as a professional chemist to come to work at Disney. He also worked in England in a similar role to the one he had at Kodak before moving to California.

There is a world of difference (the chief difference being one of credibility) from being a professional chemist to being a novice who took on the role for a short time. If Mary Weiser truly gifted in this pursuit, why would a company that’s too scared to hire the right people recruit Bianchi from Kodak a year or so after Weiser added the role of “paint chemist” to her responsibilities? I think this is a fair question even if the answer is simply that Weiser didn’t want to continue in that role.

In regard to Bianchi and his role as the Disney paint chemist, he remained at Disney from July 31, 1939 until he retired in 1978. There is a small gap in his employment (1946 on through 1948 and again in 1954), which his family told me Bianchi made for a personal reason. During that gap, Steve McAvoy was put in charge of the Disney paint lab and for whatever reason, this time period also features some of the worse quality paint made at Disney. The decrease in quality is easily noticeable.

In regard to when there is a marked noticeable improvement in the quality of Disney production paint, that change happens under Bianchi after the studio is flush with revenue from Cinderella (Clyde Geronimi, et al, 1950) and Bianchi is given money to be able to play with the paint in a new and substantial way. You see the first noticeable shift in paint chemistry in Alice in Wonderland, ((Clyde Geronimi, et al, 1951), and that version of the formula morphs during that decade in precisely the way I have observed firsthand and this was confirmed to me by Edward Bianchi.

Like with Helen Nerbovig, the Walt Disney Studio has an ugly habit of assigning tasks to people who lack the professional experience to do the jobs they’re being asked to do. You see this repeatedly at Disney with Nerbovig and Weiser, and with their staff at the Disney Animation Research Library when for example Ariel Levine was given the title of “Collection Manager” and her friend Mary Fullenweider was given the title of “Art Conservator.” As part of the hiring process, friends and neighbors of the people who run the archives or libraries at Disney and people who once had dreams of being an actor, actress, or screenwriter are told they will be a “Disney God” as part of the vetting process to work at the company.

The manifestation of leaps in logic where you let people do things when they lack any experience is not unlike when the Disney company made a 17-year long decision to put a polyester-based product called MacTac® on the front and back of their Tri-Acetate production cels. This decision was made without paying a facility to professionally test the use of MacTac® on Disney cels, or by paying a conservation scientist.

In speaking with Disney employee Merrie Laskie, who for 20 years was responsible for preparing Disney production and limited edition art for sale for the modern Walt Disney art program, Laskie told me cels with MacTac® on them were tested by leaving them on the roof of the Feature Animation building on the Disney lot where they were exposed to whatever shifts in the environment that might have happened outside on the roof of a building in Burbank, California.

I point this out not to demonize Laskie, Weiser, Johnson or anyone. Rather, to illustrate the way the studio culture progressed, where you have an emphasis at Disney on being “a team player” and protecting the decisions made by your superiors even when you sense what you are doing is wrong. Doing this does create an exaggerated sense of importance to how management feels about themselves and it also generates a meek and compliant team of people who report to management.

For the record, this was not the way to test MacTac’s compatibility. I’m saving that for part two of this article.

Instead, for here and now, I want to close this piece with a visual review of what Helen Nerbovig and her team did to Disney production art post-production and what the outcome of those choices were on the art history of Disney production art.

This is what a Disney production cel and production background should look like.

Unlike any other studio of its size, the Walt Disney Studio due to its corporate structure did things that permanently harmed their own art history. Production art was cut and glued in ways that contributed significantly to the decay of their screen used art. They put sealants on the back of the art that damaged the plastic and discolored the paint. They cut their production cels and turned them into stickers that they applied to production backgrounds using adhesives that were not adhesives. Similarly, the same medium was smeared on the front and back of their production backgrounds.

THE BEST-LAID PLANS OF MICE AND MAGIC,

THE LOST ART HISTORY OF THE WALT DISNEY STUDIO

The Courvoisier years, 1938-1946

This article is dedicated to Giannalberto Bendazzi, Italian historian and writer.

© 2024 Ron Barbagallo

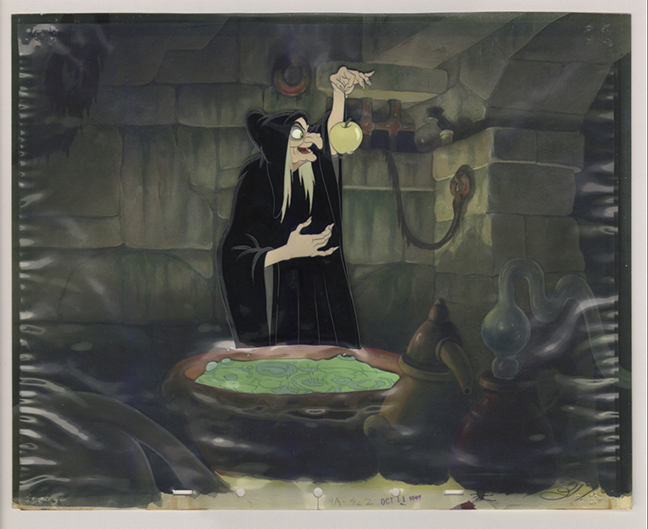

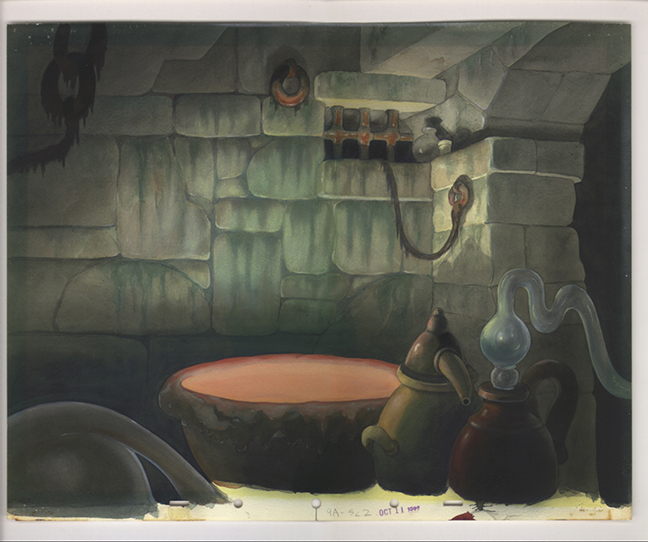

The Evil Witch with the poisoned apple at the cauldron, from Walt Disney’s feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, 1937, full production cel sheet (unrestored) and full background (unrestored).

The cel sheets are full and were unaltered from the time of production. The peg bar is complete. The opaqued paint layers are as they were at the time of production with one unfortunate exception: Both cel paintings had a sealant applied at Disney post-production put on the reverse side of their opaqued paint layer; that sealant can discolor the production paint. The background painting is on a full sheet. The background was not adhered to anything post-production. There is no fake-adhesive on either side of the background. As a result, there are no chunks of opaqued paint stuck on the background. No one added new paint on top of the cels post-production. No one added new paint on top of the background post-production.

There are cases like this where Disney production cels and background left the studio almost unmolested. This cel and background is one of those - with the exception of staples and the tapes that were added post-production to keep the elements together. Unfortunately, the face of the painting did experience some fading to that fact that dyes were added to the pigment in the paint.

The Evil Witch cel and background and the next cel and background of the Dwarfs exiting the diamond mine represent the slightest alterations to Disney art post-production.

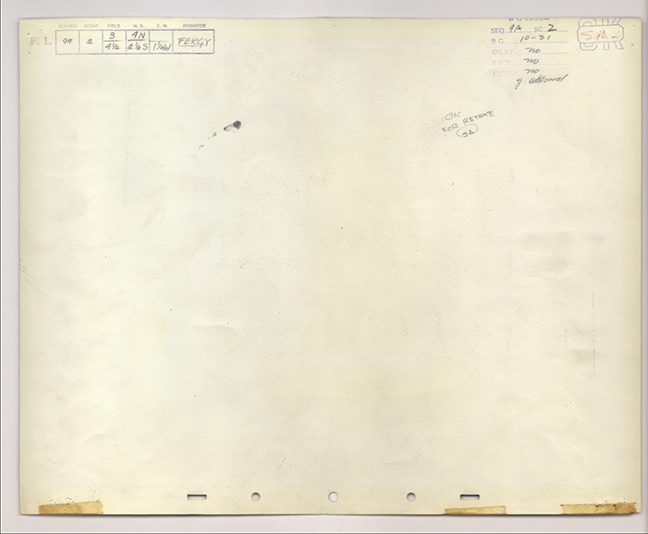

Grumpy, Happy, Sleepy, Bashful and Sneezy from Walt Disney’s feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, 1937, production cel sheet where the bottom of the sheet and the peg bar registration holes were cut off. Similarly, the bottom part of the paper background and its matching peg bar registration were cut off. There is no adhesive on the back of the art. The art was not adhered to a backing board.

This is an example of a Disney pan production background (front and back) and a key Disney production cel painting where the only alterations done to the production artifacts was the removal of the peg bar registration.

This setup is archetypal of where things started to derail. Someone inexperienced in the longevity of the materials made a collage using mismatched pieces of production art and new elements and turned production art artifacts into a collage.

Snow White, one brown bird and two bluebirds from Walt Disney’s feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, 1937, trimmed production cels applied to a handmade background not from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Sealants and something thought to be an adhesive were put on the back of the production opaquing. That background was adhered to a sheet of acidic cardboard. A clear cellulose nitrate cel sheet was placed on top. Tapes were applied to the edges.

As you can see, the cel paintings were cut down to the outline of their characters. I have been told this was done because Helen found the clear areas around the sheet distracting and that is a tragic mistake because the clear areas of the sheet are what is holding the paint layer flat. Research into the degradation of plastics was available in the 1920s so making an excuse for this is just that - an excuse.

Degradation to this sort of plastic is not unlike what you see in paper used in books from this time period. The entry point is the edge that is exposed to the elements. If you look at the Evil Witch cel setup pictured above you will see the nitrate sheet has distortion at the edges of the sheet. The degradation to this type of plastic, the tightening and the peaks and valleys, are more pronounced at those entry points.

Of equal concern is how compromised the production opaqued paint on the reverse side of the cel painting. Post-production someone at Disney applied a sealant over the opaqued paint which discolored the paint and to make matter worse, they added a fake-adhesive which further distorted the colors of the opaquing. There are also many occasions where the sealant added physically distorted the plastic. The uninformed practice of trimming cels and adhering cels to whatever you wanted was legitimized by Disney at this time and it not only continued at Disney up until the Who Framed Roger Rabbit, (Robert Zemeckis, 1988) auction at Sothebys (June 28, 1989) - but it taught generations of gallery owners that they could cut cels up and glue cels to whatever they wanted in order to make a buck.

This is what the front of the Snow White cel and the fronts and backs of a handmade background from Disney look like due after the fake-adhesive was liberally splashed all over the place. As you can clearly see, the fake-adhesive bleed from the back through to the face of the paper and it did not secure the airbrushed paper background to the thick piece of acidic board that was put behind it - because it is not an adhesive. Another post-production alteration is the cel painting of Snow White had a layer of dark post-production airbrush applied on top of all the production paint.

I’ve not included the trimmed cels depicting the two bluebirds and the brown bird here because none of those cels are key to this cel setup. One of them appears that it could be from this scene. The others certainly are not.

As can be seen clearly here, after the studio stopped using cellulose nitrate cel sheets to make art, they leaped onto a morphing number of poorly manufactured plastics. While they did this, they continued the practice of cutting the cel paintings down around the perimeter of the characters. And the degradation to the plastics, despite this being a different plastic, is similar in what it does as it ages with several key exceptions: The distortion to the plastic is worse. The damage done by the application of post-production sealant to the plastic is worse. The damage done to the integrity of the opaqued paint layer can be extreme at times but is similar to what happened with the cellulose nitrate cel paintings that were similarly altered post-production.

One of the truly disturbing things about this particular cel setup is: The background painting is from Pluto’s Judgement Day, (David Hand, 1935), the cel of Minnie Mouse is from Mickey’s Birthday Party, (Riley Thomson, 1942). The cel of Mickey Mouse is from a much later era and remains unidentified. Mickey was painted on a different plastic than the other two cels. The cel depicting Pluto is from an unidentified short but is more period correct than the one depicting Mickey Mouse. Having said all that, this is a great example of how Disney put whatever production art they had together without taking the slightest care that none of these elements belong together.

And on that note, allow me to show you other examples of Walt Disney production backgrounds that were molested post-production in order to sell the art.

On the left, is a screen shot from Walt Disney’s feature film Dumbo (Ben Sharpsteen et al, 1941). On the right is what happened to that production background painting. It was not cut down - but new paint was heavily added to crudely create a new image. Not only the decorative drybrush bubbles - but a very thick amount of brown paint was added on the bottom which was supposed to turn the bedsheets and pillow background into an exterior tent background. As is always the case with trimmed cels you will find lots of fake-adhesive used to adhere the trimmed cel of Dumbo (not shown) to the background.

Well, maybe this was an isolated case?

This is NOT an isolated case. This is more times than not "the" case. On the left is a well-known scene from Walt Disney’s feature film The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, 1949 and on the right what someone at the studio did to it. Not only did they adhere cut-up cels of Chip and Dale from 1952 short subject Pluto’s Christmas Tree (Jack Hannah, 1952) but they painted right on the background to make it look like they were kicking up snow.

This piece arrived with a post-production piece of wood pulp board adhered behind the Mr. Toad background painting. The edges of the paper are acid burned and discolored from being in proximity to this board.

Yeah, but they wouldn’t cut down important production backgrounds and use them any which way they could? Would they?

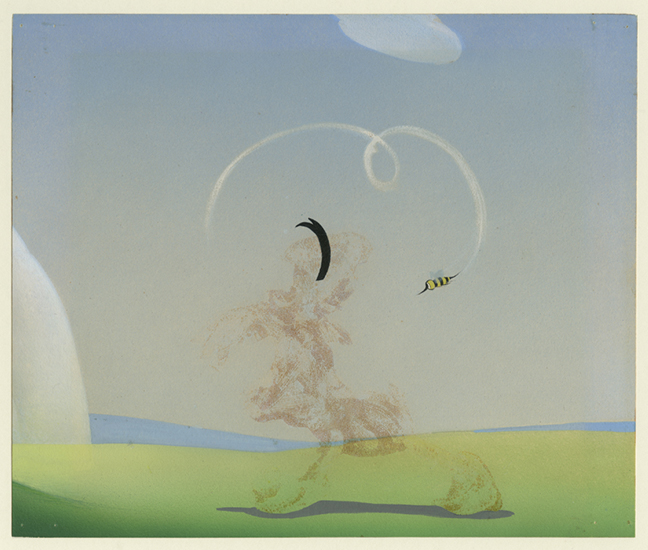

Actually, they frequently cut down wonderful and important pan backgrounds from feature films and short subjects and put cels trimmed down to the outline of their character right on top of them. On the top is a screen shot from The Reluctant Dragon, (Hamilton Luske et al, 1941). Under it, on the bottom, is a piece of that background (partially restored). This part was the left part which was cut off the pan background so a trimmed cel of Donald Duck from Donald’s Camera, (Dick Lundy, 1941) could be glued on top of it. A bee was painted post-production right on the background. So a black ribbon and a white swirl indicating the bee’s path. A strange opaque gray shadow under Donald was also painted right on the background. And of course the fake-adhesive (partially extracted here) was smeared right on top of what was left of this pan background painting.

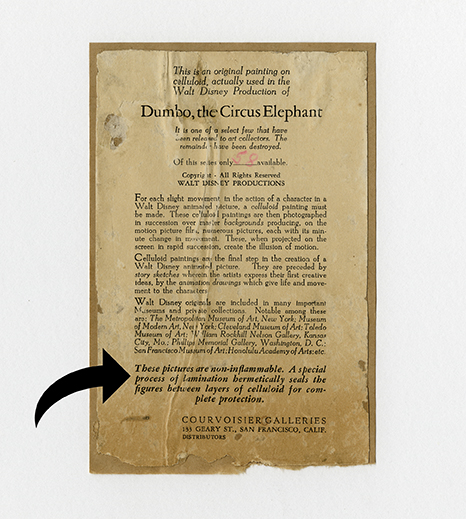

And lastly, and maybe most importantly from this date moving forward, there are the solvent-based laminated Disney cel paintings that the Walt Disney Museum suggests were laminated in San Francisco but Buf E. Nerbovig says were laminated at Disney. Lets start by what Disney claimed in writing their lamination process was doing.

“These pictures are non-flammable. A special process of lamination hermetically seals the figures between layers of celluloid for complete protection.”

“Complete protection” is what Disney claimed would happen.

But this is what happened instead:

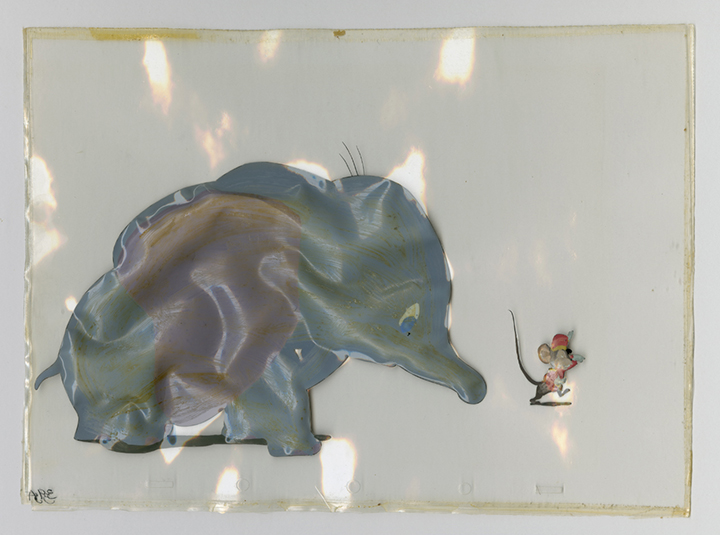

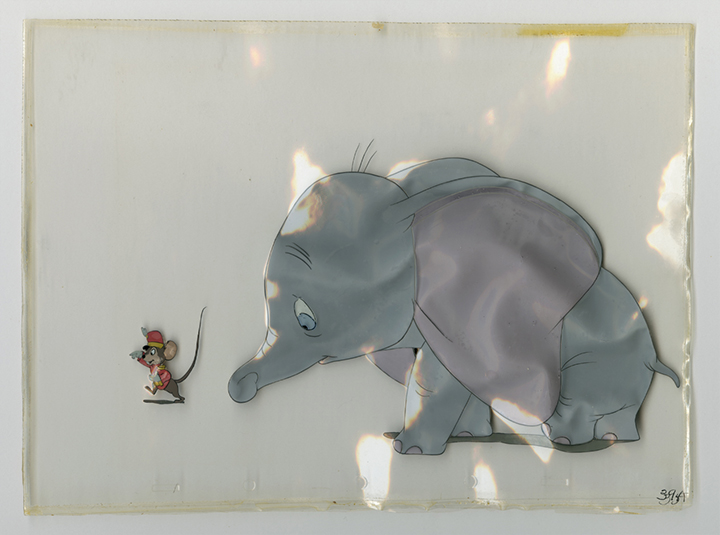

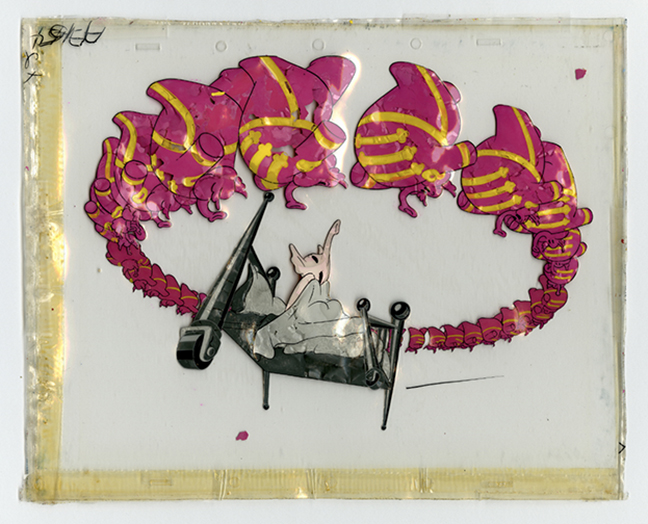

As you can see, this is a cel sheet composite depicting art from Dumbo, 1941 and in this case, this is 4-sheets of Disney Di-Acetate that were laminated at Disney. The plastic has physically shrunk quite a lot. While I don’t know for a fact that the plastic used to be the exact size of the Disney prepared background painting, but I do know from my work, that this plastic is the one used by Disney that shrinks quite a lot. It can be theorized with some authority that it probably used to be a size similar to the background and this is because the tape used to adhere the cel to the back of the background left an layer of adhesive on the edge of the cel sheet composite. That tape sprang free due to the shrinkage of the plastic, leaving the laminated cel composite loose in its housing.

Well, maybe this is an isolated case? Maybe the owner of the artwork did something to the art?

No. This is not an isolated case. This is actually THE CASE. Here is another laminated cel sheet composite from Dumbo, 1941. It is also 4-sheets of Disney Di-Acetate. 4-sheets are not always the case. 3-sheets composites are more common. 5-sheets are not unheard of.

This is 5-laminated cel sheet composite from Dumbo. Please note: the ambered colored tape on the edges of the cel setup are not typical of tape used at Disney. Nor is this type of tape recommended. As you can see clear cel sheets used to laminate the art come with Disney peg bar registration. They are also chemically identical to cel sheets known to be used by Disney to make cel paintings for Disney’s 1941 feature film Dumbo.

Yeah, but Disney couldn’t have done any other weird things to their art post-production, right?

And - Wrong! Yes, they did.

This is a 3-laminated cel sheet composite from Dumbo, 1941. And it is a Disney cel painting depicting 14 circus clowns from Dumbo. The cel painting has been - trimmed around the outline of characters - and after someone at Disney cut the cel up, someone decided maybe they should have left the cel was better on a larger sheet so they laminated the cut element between two clear cel sheets from Disney! Be sure to look at the peg bar registration over to the far right.

But laminating the cels can’t mean none of them were “hermetically sealed between layers of celluloid for complete protection?”

Actually, YES, this is exactly what it means.

And it is simply a matter of time. The cel paintings that feature larger areas of opaquing are and will continue to deteriorate and this will cause wild areas of distortion to the acetate, a softening of the acetate, and severe cracking to the opaqued paint. This will happen to cels where the opaquing is of smaller characters too. That is coming later. Also, which pigments are involved do factor in the way the paint interacts with some of the off-gassing particles.

This is the best example of what is happening now and what is coming down the road:

This is the same 4-laminated cel sheet composite from Walt Disney’s 1941 feature film Dumbo.

The image on the left was captured in 2003. The image on the right was captured in 2017.

This laminated cel and background were kept in temperature and humidity controlled environment and in a housing made by me - and the lamination process continued to damage the opaqued painting layer because the lamination process did not allow the paint layer to perform as Emilio Bianchi designed the paint layer to perform. Time and time again, this is where the way things are done at Disney is tied to the insecurities of the people in their corporate culture and how people who are told to do certain jobs may or may not have the ability to handle those tasks.

Summary:

Understanding the value of art history and preserving it comes first for those of us who respect the artifact as fine art. So when important art history is treated like this and so many rationalizations are offered as a way to excuse how the art was treated, the reality of what the art was turned into truly hurts.

But the bottom line is the history of Disney art is a history about money and the Peter Principle first, and you can talk yourself blue in the face before anyone will listen to any other thread of logic and that is because culture at Disney grooms its employees and Disney publicity grooms the studio’s fans to believe what the studio needs them to believe so the company can make money.

For these reasons the lost art history of Disney art remains a place where the best laid plans of mice and magic are on one side of the discussion, and the decaying legacy of what happened to the company’s production art is on the other.

Acknowledgments:

This article could not have happened without the career long help of conservation scientist Michele Derrick, my friends Robert Aitchison, Doug Nishiumura and Steve Weintraub.

I additionally want to thank Giannalberto Bendazzi who asked me to author something like this a few years back and Christopher Holliday for getting me to do it.

Additional thanks go to Grégoire Philibert and Barbara Brown, and my continued gratitude to Jim Walker, Marco Bellano, Greg Dyro and Lance Watsky for their guidance and help.

The images are the property of The Research Library at Animation Art Conservation, © Ron Barbagallo. The characters in the art are © Disney Enterprises Inc.

This article is owned by © Ron Barbagallo.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You may not quote or copy from this article without written permission.

YOUR USE OF THIS WEBSITE IMPLIES YOU HAVE READ AND AGREE TO THE "COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS" OF THIS WEBSITE DETAILED IN THE LINK BELOW:

LEGAL COPYRIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS / TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF USE

INSTRUCTIONS ON HOW TO QUOTE FROM THE WRITING ON THIS WEBSITE CAN BE FOUND AT THIS LINK.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE JPEGS IN ANY FORM OR COPY ANY LINKS TO MY HOST PROVIDER. ANY THEFTS OF ART DETECTED VIA MY HOST PROVIDER WILL BE REPORTED TO THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, WARNER BROS. OR OTHER LICENSING DEPARTMENTS.

ARTICLES ON AESTHETICS IN ANIMATION

BY RON BARBAGALLO:

The Art of Making Pixar's Ratatouille is revealed by way of an introductory article followed by interviews with production designer Harley Jessup, director of photography/lighting Sharon Calahan and the film's writer/director Brad Bird.

Design with a Purpose, an interview with Ralph Eggleston uses production art from Wall-E to illustrate the production design of Pixar's cautionary tale of a robot on a futuristic Earth.

Shedding Light on the Little Matchgirl traces the path director Roger Allers and the Disney Studio took in adapting the Hans Christian Andersen story to animation.

The Destiny of Dalí's Destino, in 1946, Walt Disney invited Salvador Dalí to create an animated short based upon his surrealist art. This writing illustrates how this short got started and tells the story of the film's aesthetic.

A Blade Of Grass is a tour through the aesthetics of 2D background painting at the Disney Studio from 1928 through 1942.

Lorenzo, director / production designer Mike Gabriel created a visual tour de force in this Academy Award® nominated Disney short. This article chronicles how the short was made and includes an interview with Mike Gabriel.

Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, an interview with Graham G. Maiden's narrates the process involved with taking Tim Burton's concept art and translating Tim's sketches and paintings into fully articulated stop motion puppets.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse Of The Were-Rabbit, in an interview exclusive to this web site, Nick Park speaks about his influences, on how he uses drawing to tell a story and tells us what it was like to bring Wallace and Gromit to the big screen.

For a complete list of PUBLISHED WORK AND WRITINGS by Ron Barbagallo,

click on the link above and scroll down.